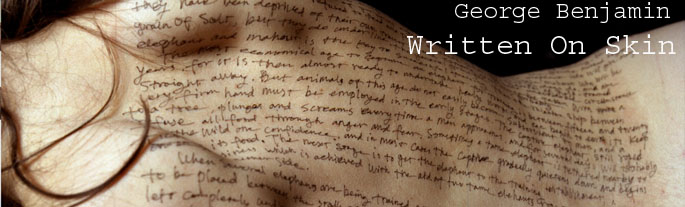

Sparking an instantaneous standing ovation at its world premiere performance last night, Written on Skin is almost certainly headed straight for any list of the best operas of the 21st century so far. Fairly short, at just over an hour and a half, sung in English, and almost unbearably intense, the new opera by British composer George Benjamin and his compatriot, playwright Martin Crimp, is based on the 13th-century Occitan legend of the poet and troubadour Guillem de Cabestany, a tale that turns up in various forms in Petrarch's The Triumph of Love, Boccaccio's Decameron, Ezra Pound's Cantos and Stendhal's On Love: in love with Seremonda, Cabestany is killed by her jealous husband Raimon, who then feeds the dead poet's heart to his unsuspecting wife; when he tells her, she throws herself out of a window to her death.

Sparking an instantaneous standing ovation at its world premiere performance last night, Written on Skin is almost certainly headed straight for any list of the best operas of the 21st century so far. Fairly short, at just over an hour and a half, sung in English, and almost unbearably intense, the new opera by British composer George Benjamin and his compatriot, playwright Martin Crimp, is based on the 13th-century Occitan legend of the poet and troubadour Guillem de Cabestany, a tale that turns up in various forms in Petrarch's The Triumph of Love, Boccaccio's Decameron, Ezra Pound's Cantos and Stendhal's On Love: in love with Seremonda, Cabestany is killed by her jealous husband Raimon, who then feeds the dead poet's heart to his unsuspecting wife; when he tells her, she throws herself out of a window to her death.

The stylized opera transforms the troubadour into a young painter of illuminated manuscripts - The Boy - hired by a wealthy feudal lord - The Protector-to produce a glorifying biographical book; living in their manor, the Boy awakens the repressed passion of the lord's young wife - Agnes, or The Woman—and possibly of the brutal Protector himself, as the story proceeds to its inexorable end. Given a post-modern twist, the opera sets it all up as a tale within a tale, told in 15 short scenes, narrated by a mini-chorus of "angels" in modern dress. At times the three protagonists recount their own actions in the third person, while the angels and a small band of assistants rush in to move both props and protagonists around between scenes.

The simple set, clearly divided into the modern white costume and prop rooms and the old gray-walled manor halls, makes the tale-within-a-tale conceit quite clear. Like most contemporary operas, Written on Skin—the title refers to manuscript parchment—doesn't venture into anything resembling an aria, but puts its dramatic, cinematic, percussion-filled music and difficult sung-through dialogue at the service of the relentlessly grim plot. There's no nudity or even much bared flesh, but several sexually explosive scenes might be the most explicit actually written into any opera. There are hints of Benjamin Britten and Ingmar Bergman here and there, an echo of Gregorian chant and a faint flash of madrigal; it's powerful, violent and, toward the very end, overplayed with a slightly hamfisted hand.

Staged by Katie Mitchell and brilliantly sung by a nearly flawless cast, opening night was a collective tour de force. With his slightly eerie, ethereal voice and his head shaved bald, American countertenor Bejun Mehta plays the Boy as a mysterious, inscrutable stranger, not even remotely boyish. British baritone Christopher Purves is a forceful and frightening ogre as the Protector, although his beautiful voice seems to find lilting melody even where there is none. And Canadian soprano and consummate actress Barbara Hannigan, a contemporary music specialist, outdoes even her virtuoso reputation with an emotionally shattering performance that will surely define the role of Agnes for many years to come.

Written on Skin was commissioned by the Festival d'Aix-en-Provence in cooperation with the Nederlandse Opera Amsterdam, the Theatre du Capitole de Toulouse, the Royal Opera House Covent Garden London and the Teatro del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino.

Written on Skin is George Benjamin's longest span of music to date at 95 minutes and is scored for an orchestra of 60 players with some unusual additions including a bass viola de gamba and a glass harmonica. Nimbus hope to record 'Written on Skin' this summer and release it in time for the performances in London next year. George Benjamin has been an exclusive Nimbus artists for more than thirty years and this month his entire discography is on sale.

Read the Financial Times interview between George Benjamin and Richard Fairman entitled Let there be light where they discuss Benjamin's thoughts on the new opera 'Written on Skin' and a week long series of his music at the South Bank, London in May 2012.

'Benjamin is a composer who is like the eye at the centre of the contemporary music storm.' Richard Fairman, Financial Times, London, March 2012